During the chilly spring of 2013 I was a humanitarian aid worker waiting for my next mission. Didn’t yet know where I was going but I was busy preparing to lease my flat for the upcoming departure. As I spent my days carrying books to the basement and cleaning out wardrobes – I did this regularly, then carrying everything back up a few months or a year later – I was suddenly accompanied by a newly made friend of mine. A young Syrian woman who decided to drop out of the human rights program she had been brought to Sweden to attend, and apply for asylum.

“I’m leaving this place tonight,” she said on the phone in a hushed voice. We hung out quite a lot, and had known each other since the year before.

“Where are you going to stay?”

“I don’t know.”

“Come here.”

My friend was a beautiful young woman, intelligent and charismatic. But that evening when she showed up with a hastily packed suitcase, other adjectives would have to be used to describe her appearance.

I did what I usually do when someone moves in with me with short notice; made tea, brought out blankets and a towel. My living room couch was used to hosting people, it actually never complained once, but it had never served someone with so many raw emotions, energy and anxiety at the same time.

“You’re safe here”, I tried to comfort my friend that very first night, not knowing if I meant safe at my place or in Sweden.

Fear was nothing new to her. She had after all one of the most dangerous jobs a person can possibly have – the one of being a journalist in Syria. But neither she nor I had thought that the threat of the regime could exist in the form of individuals in Sweden.

I too was uncomfortable being around this individual, and we agreed not to let anyone know that she was staying with me. Now 11 years have passed, and it’s safe to tell the story.

As we spent most of our time together in my small flat during that chilly month in spring, we started to get to know each other better, and quickly resumed some kind of schedule.

“What are we watching tonight?” she would ask, as she was preparing plates of fruits, biscuits, cheese – much needed plates since we always stayed up late. Sometimes the snacks were accompanied by a bottle of wine if we could afford it; her monthly grant as an asylum seeker had yet to be started.

As we worked our way through seasons of Girls, she started to share more about herself. Her stories were incredible, but she had no idea:

She had been on a journalistic assignment covering the war, when she and the cameraman had to flee by car from people sent out to arrest them. In a hospital they had been able to take cover. She remembered her mouth being so dry that she couldn’t speak.

When her blog where she wrote about the war crimes committed by the regime became famous, she was arrested with her baby, and it was someone close to her who had snitched, letting the regime know where she was staying.

During her arrest protests had been organized to demand her release. She showed the online posters with her name and photo – this later became useful evidence in her asylum case.

Listening to her stories of amazing courage became a crash course in the Syrian uprising and taught me how to recognize common patterns – phrasing, reasoning – of Syrian activists trying to bring down the regime. These skills would turn out to be useful later on. I could be accused of many things but not that one of being a bad listener. Or writer.

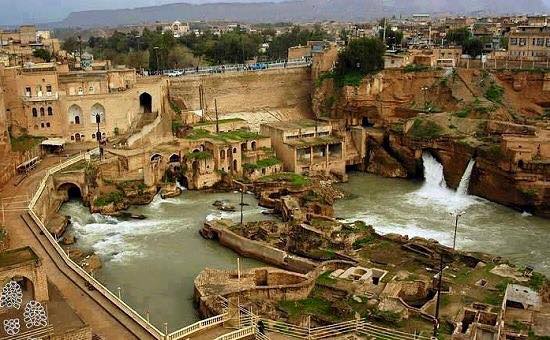

I had been to Syria before the war and I could relate to her description of her beloved country. Have you ever smelled the jasmine flowers of Damascus in summer? Have you watched the water pass by in the water wheels of Hama? Those are beautiful sights. I would say it’s impossible to visit Damascus and not fall in love with the city and the people. The beauty infiltrated, though, by the underlying threats of violence – a violence not only directed towards political opponents.

One story I was told by a pro-regime friend said how the ruling family had a part in organizing kidnappings of young, Syrian girls for wealthy men; their mutilated bodies dumped afterwards in lakes, attached to weights.

“I want to go home”, my friend often said.

I thought that she would if only she was patient. Much like the people that I got to know in those early years of the revolution, I believed that the Syrian opposition had the strength to overturn a sadistic regime.

Sure, the opposition was fragmented, without a clear hierarchy, and there was worrying news about extremist groups funded from the outside. But the Arab spring was hopeful. Areas in Northern Syria were taken over by the opposition; the Kurds had support from the other Kurdish regions. The activists I knew were intellectual, reflecting, with a deep longing for freedom and the right to live a life without fear. They must be able to do the change, right?

It wasn’t always easy to host my friend, but I dealt with enough traumatized people to have some tools and boundaries. To help her cope we went out, went to my friends’ parties, cooked dinners.

Did I mention that she was beautiful? Her looks were actually amazing. Going with her somewhere, people stopped and stared; men kept calling and asking her out. One man was stupid enough to message me on Facebook, asking to wire me money so I could buy her flowers. I agreed, cashed out, we spent the money on ourselves.

We also loved watching silly movies. One favorite was Crash – when the main character in a rehab center wrote a letter of apology, admitting he was alcoholist and didn’t want to be anymore, we changed the lines to the certain individual she had fled from:

“I’m sorry I pretended to be your friend so I could spy on you for the mukhabarat!” she exclaimed.

“I don’t wanna be an undercover agent for the Assad regime no more!” I latched on, and we laughed hysterically.

So why did I do what I did a few months later? Why did I write the articles that I did? Syria is not my country. I lost friends, pro-regime Syrians, because of it. They saw me as a traitor, someone interfering in an issue that wasn’t mine.

It was not planned in advance. My friend was, of course, an influence. But also because of her many compatriots that I connected with, my love for them and the country. Syria did not deserve the terror that was brought onto them because they demanded what some take for granted: a system not deflated by corruption; wages enough to live and not only survive on; the right to live a life free of fear.

And we believed in change, I believed in change. If enough stories came out about the war and the crimes against humanity being committed there would be little chance for the Assad family to stay in power. They would sooner or later leave the country on a private jet heading to Riyadh and never come back, finally giving up a power that was never given to them by the public.

The day came when I got the call about my assignment. In the evening, my friend asked where I was going.

“Can you have a seat?” I told her.

Confused, she sat down on one of the kitchen chairs, it was one of the few items in my now empty flat that hadn’t been moved to the basement.

“Why? Where are you going?”

I hesitated slightly. Then replied.

“Damascus.”